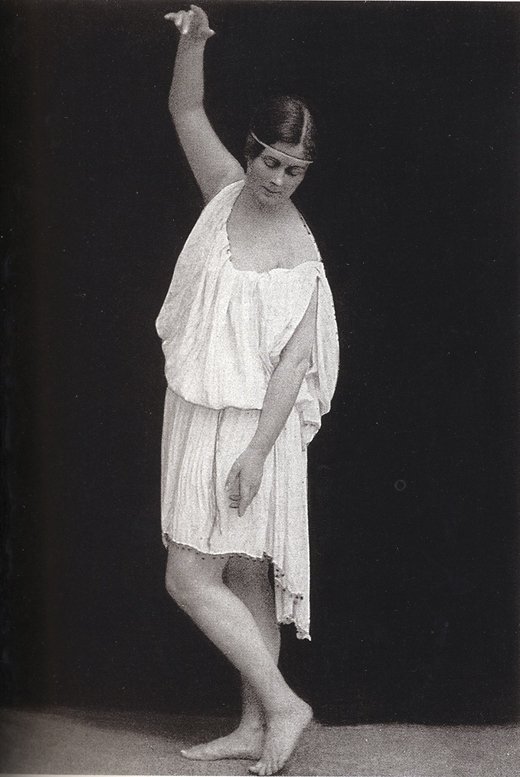

Isadora Duncan

About Isadora Duncan

Isadora Duncan (1877-1927) was an American pioneer of dance and is an important figure in both the arts and history. Known as the “Mother of Modern Dance,” Isadora Duncan was a self-styled revolutionary whose influence spread from American to Europe and Russia, creating a sensation everywhere she performed. Her style of dancing eschewed the rigidity of ballet and she championed the notion of free-spiritedness coupled with the high ideals of ancient Greece: beauty, philosophy, and humanity. She brought into being a totally new way to dance, and it is this unique gift of Isadora Duncan that the Isadora Duncan Dance Foundation wishes to preserve, present, and protect.

Dancer, adventurer, and ardent defender of the free spirit, Isadora Duncan is one of the most enduring influences on contemporary culture and can be credited with inventing what came to be known as Modern Dance. With free-flowing costumes, bare feet, and loose hair, she took to the stage inspired by the ancient Greeks, the music of classical composers, the wind and the sea. Isadora elevated the dance to a high place among the arts, returning the discipline to its roots as a sacred art. Duncan shed the restrictive corsets of the Victorian era and broke away from the vocabulary of the ballet. Stepping out of the dance studio with a vision of the dance of the future, Isadora embraced artists, philosophers, and writers as her teachers and guides.

According to Isadora, the development of her dance was a natural phenomenon – not an invention, but a rediscovery of the classical principles of beauty, motion, and form. Her dances were born of the impulse to embrace life’s bittersweet challenges, meeting destiny and fate head-on in her own whirlwind journey, filled with both tragedy and ecstasy. She was determined to “dance a different dance,” telling her own life story through abstract, universal expressions of the human condition.

Shocking some audience members and inspiring others, Isadora posed a challenge to the prevailing orthodoxies of her time. Isadora was a champion in the struggle for women‘s rights. Many saw a glorious vision for the future in Isadora’s choreography. Her influence upon the development of progressive ideas and culture from her time to our own has yet to be measured. She has inspired artists, thinkers, and idealists everywhere.

Isadora Duncan was born in San Francisco, California on May 26, 1877, the youngest of four. Her parents were divorced by 1880 and her mother Dora moved with her children to Oakland, where she struggled to make ends meet as a piano teacher. Mrs. Duncan spent her evenings reading aloud to her “Clan Duncan”, the works of Shakespeare, Browning, Shelley, Keats, Dickens, Ingersoll, and Whitman; sowing the seeds of artistic inspiration in her youngest child, Isadora. In her early years, Isadora attended school but found it stifling and dropped out at the age of ten to be self-educated at the Oakland public library under the guidance of poet-laureate Ina Coolbrith. Ever resourceful, Isadora and her sister Elizabeth earned extra money by teaching dance classes to local children. After a series of ballet lessons at age 9, Isadora proclaimed ballet a school of “affected grace and toe walking,” and quit. Later, in her autobiography My Life, Isadora wrote that in her opinion, ballet training resulted in the look and feel of an “articulated puppet…producing artificial mechanical movement not worthy of the soul.”

In 1895, with a voracious appetite for art and life, Isadora traveled first to Chicago, and then to New York and by 1899 she moved to Europe to continue developing her art.

During her youth in San Francisco, Isadora had already formulated her signature movement style. As she matured, she developed her choreography and started setting her dances to early Italian music, with costumes and dance motifs inspired by Renaissance paintings and ancient Greek myths. As a “California novelty” Duncan was invited to perform for salons and garden parties by wealthy patrons of the arts. She was often met with opposition and ridicule. One society lady is known to have remarked, “If my daughter dressed like Miss Duncan I would lock her up in the attic!” Isadora struggled financially but rejected invitations to perform in vaudeville circuit variety shows.

Eventually, this original and intrepid Californian caught the attention of the Hungarian press. In 1902 her debut performances in Budapest with a full orchestra were a critical success and ran sold-out for 30 days. Her encore was Johann Strauss’s popular and intoxicating waltz The Blue Danube.

Within two years of performing her own choreography, Duncan had achieved both notoriety and success. At this point, she could afford to take her spiritual pilgrimage to Greece, realizing her life’s dream to touch the sacred marble of the Acropolis and steep herself in the ancient mysteries of Greek art and architecture.

In 1905, Isadora settled in Gruenwald outside of Berlin and opened her first dance school. She subsidized the entire establishment with proceeds from her tours. Along with her sister Elizabeth, she started training the young dancers who would become her performing company, “The Isadorables,” as dubbed by the press. Initially, she enrolled twenty girls and boys, but her effort to include boys was unsuccessful and was finally dropped due to a lack of funds.

By this time, Isadora had begun to achieve celebrity status among the artistic and cultural illuminati of her day. Auguste Rodin, Michel Fokine, Vaslav Nijinsky, and Gertrude Stein all paid tribute to her in sculpture, choreography, and poetry. When the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées was constructed in 1913, Isadora’s image was sculpted by Antoine Bourdelle for the facade and murals in the auditorium.

Duncan had vowed never to marry, but out of wedlock, she had a daughter named Deirdre whose father was the famous set designer, Edward Gordon Craig. Although their passionate love affair ended after several years, he was to remain her lifelong friend. Her second child, Patrick, was fathered by a wealthy heir to a sewing machine fortune named Paris Singer. Singer underwrote the founding and operation of another of Duncan’s second school prior to World War I in Bellevue, just outside of Paris. Later, in 1913, Deirdre and Patrick drowned with their nanny as their car rolled into the river Seine. Isadora was devastated. Her dances Mother and Marche Funebre, featuring music by Scriabin and Chopin respectively, were inspired by her loss and conveyed her heartbreak on a universal level.

Picking up the pieces, Isadora retreated to Italy to spend time with her friend Eleanora Duse, and started work on choreography set to Schubert’s 9th Symphony and Tchaikovsky’s 6th Symphony. Between 1916 and 1920, she performed solo and toured extensively across Europe and America, including one sojourn to South America.

Isadora was greatly taken with the social and political revolution that led to the creation of the Soviet Union. Believing that she could contribute to the development of a free and heroic society, Duncan followed her conviction and passion to Moscow in 1921 to make arrangements with the new government to found a new school of dance. She longed to “give her art in exchange for a free school,” and to “teach a thousand children.” Operating the Moscow school with help from Isadorable, Irma Duncan, Isadora experienced one of her most artistically prolific and critically successful periods. Timeless and mature works including The Revolutionary with music by Scriabin and a suite of dances set to Russian work songs communicate her fury at social injustice, her empathy with human suffering, and her faith in the power of perseverance to overcome obstacles. In Moscow, Isadora met the young poet Sergei Esenin and broke her previous vow by marrying him in order that he be allowed to travel with her during a tour of America. America denounced Isadora’s outspoken love of Russia but Duncan was unrepentant: “Yes, I am a revolutionist,” she said to the press, “All true artists are revolutionists.”

Isadora Duncan’s death was as dramatic as her life. On September 14, 1927, she encountered a young driver in Nice, France and suggested he take her for a spin in his open-air Bugatti sports car. As the car took off, she reportedly shouted to her friends, “Adieu, mes amis, je vais a la gloire!” — “Goodbye my friends, I go to glory!” Moments later, her trailing shawl became entangled in the rear wheel, breaking her neck instantly.

Despite Duncan’s untimely death, her legacy continues to inspire contemporary artists and boundary-breaking minds around the world. Early in Isadora’s career, sculptor Laredo Taft had described her as “Poetry personified. She is not the tenth muse but all nine muses in one.” And so it was. There are over 40 books about Isadora Duncan, countless drawings, paintings, and sculptures, two major motion pictures, a dozen TV documentaries, and several plays and poems.